Influenza - the Disease

What is influenza?

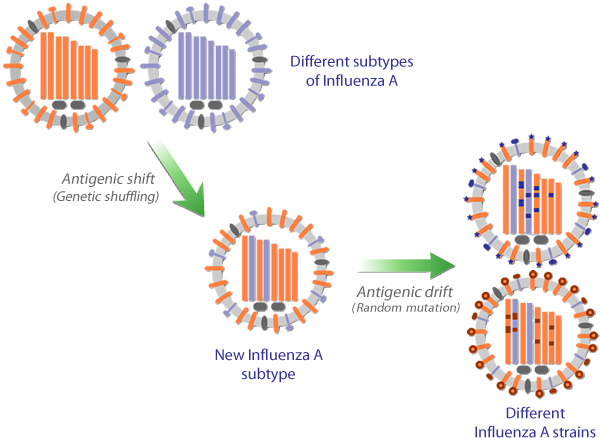

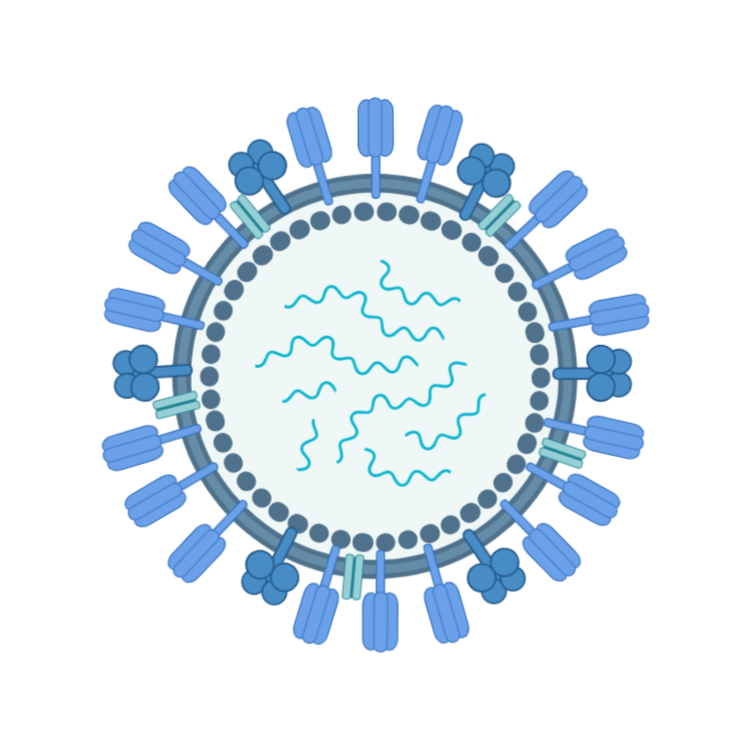

Influenza, often referred to as 'the flu', is a respiratory infection caused by a member of the influenza virus family. Influenza virus infections are usually more severe than other respiratory virus infections, and typically involve a combination of respiratory (cough, sore throat) and constitutional (fever, headache, muscle aches) symptoms. In older adults and people with certain pre-existing medical conditions, influenza infections can lead to serious and even life threatening complications. A notable feature of influenza is that repeated infections can occur throughout life.

How is influenza spread?

Influenza is transmitted by tiny droplets of moisture from the respiratory tract of infected people spread by coughing, sneezing, touch or even talking. When these are breathed in by a susceptible person, the viruses they contain can enter the cells of the respiratory tract and multiply. The person will usually become ill within 2–3 days but may be contagious and start shedding virus for up to a day before symptoms are noticed.

When is the influenza season?

In temperate regions of the northern and southern hemispheres, the main influenza season falls around the winter months (November – April for northern hemisphere, May – October for southern hemisphere) with sporadic infections at other times. In regions closer to the equator, influenza may occur throughout the year and some tropical countries may experience two peaks of activity annually.

Who is at greatest risk from influenza?

Older adults (in most countries defined as 65 years and above), people with chronic cardiac, respiratory, kidney, metabolic (eg. diabetes) and immune system diseases, pregnant women, and people in long-term care have a higher risk of severe influenza. Infants under the age of 6 months may also be at increased risk but cannot be protected by current vaccines.